The Global Spread of H5N1 Avian Influenza: Tracking Recent Outbreaks and Challenges

Introduction

Emerging infectious diseases pose significant threats to both animal and human health. The recent emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b has led to substantial mortality across various species globally. This clade has spread widely, affecting new mammals and posing risks to wildlife, farming, and human health. Before 2020, H5N1 was mainly found in Asia and poultry, but its recent spread has raised major concerns.

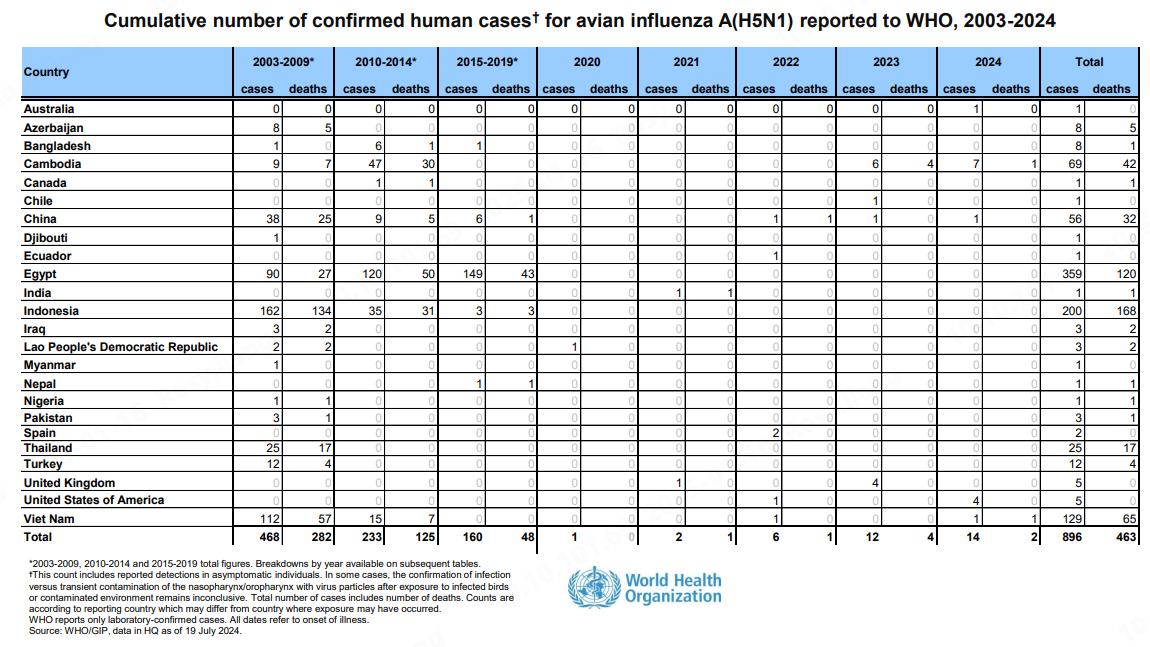

Since its discovery in 1996, H5N1 has infected over 800 people worldwide as of 2024, with a mortality rate exceeding 50% [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has documented a steady rise in human cases, highlighting the need for robust surveillance and response mechanisms.

Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for H5N1 from 2003-2024, Source: WHO

Recent Outbreaks and Human Cases

In 2014, an H5N1 virus lineage originating from Asia was first introduced to North America [2,3]. The CDC reported a series of natural infections with HPAI H5N1 virus lineage H5 clade 2.3.4.4b in terrestrial wild mammals in the United States, concurrent with high levels of circulating HPAI viruses in wild birds during the spring and summer of 2022 [4]. In 2024, human cases reported in the United States raised global concern. Below are the key cases reported in 2024:

March 2024: A Texas dairy farm worker with ocular discomfort tested positive for H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b on April 1 [5]. Only conjunctivitis was reported. The virus was later detected in over 900 dairy farms across 16 states, with California having the highest incidence (80% of cases).

May 22, 2024: First Michigan human case reported, linked to the dairy farm outbreak. Patient had mild conjunctivitis; ocular swabs tested positive for H5N1 [5]. Genomic analysis showed genotype B3.13, clade 2.3.4.4b with no significant mutations for human transmission.

May 30, 2024: Third Michigan human case reported with respiratory symptoms and ocular discomfort. Nasopharyngeal swabs tested positive for H5N1, confirming genotype B3.13, clade 2.3.4.4b [5].

August 22, 2024: First Missouri human case with unknown infection source. Two suspected human-to-human transmission cases identified. Genomic analysis revealed HA mutations (A156T, P136S) not previously seen in humans, potentially affecting vaccine interaction and transmission [5].

November 13, 2024: Canada reported severe H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b D1.1 in a teenager with no exposure history. Symptoms included conjunctivitis, fever, and pneumonia. Key mutations (positions 226, 190, H3 numbering) indicated higher human transmission risk [7].

December 18, 2024: First severe Louisiana H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b D1.1 case reported in an elderly individual who died on January 3, 2025. HA mutations (A134V, N182K, E186D) suggested enhanced human receptor binding [5].

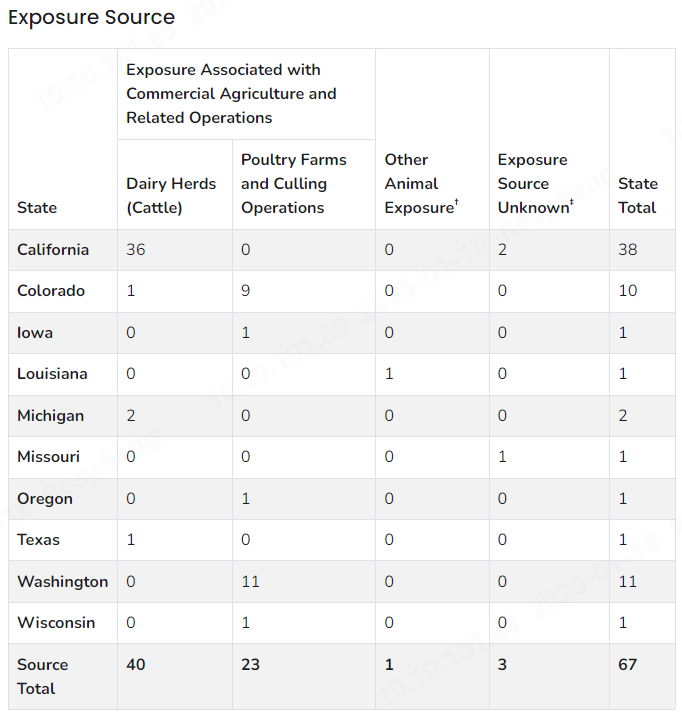

As of January 15, 2025, the CDC had reported a total of 67 human cases of H5N1, with one fatality [5].

Confirmed human case summary since 2024, Source: CDC

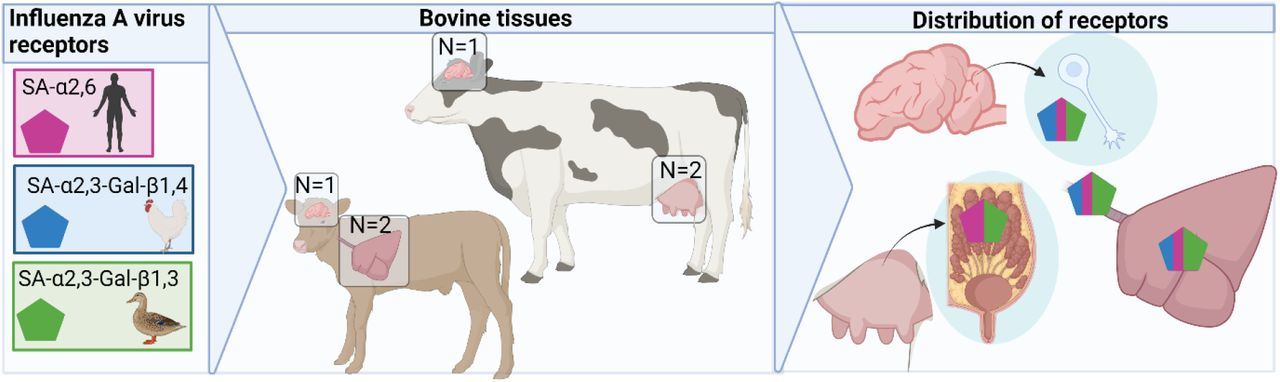

Adaptation and Evolution of H5N1

For H5N1 to become a pandemic, a critical evolutionary challenge is changing its binding preference to α2,6-linked sialic acids, which are common in the human upper respiratory tract [8]. Research shows that cows have both SA-α2,3 and SA-α2,6 sialic acid receptors in their mammary glands, making them potential sites for viral mixing and adaptation [9]. This suggests that cows could serve as mixing vessels for influenza viruses, accelerating H5N1's evolution to adapt to humans.

On December 18, 2024, the Louisiana human case showed mutations (A134V, N182K, and E186D) that make the virus bind more easily to human receptors [5]. As the flu season progresses, co-infections with seasonal and avian flu in humans or pigs could speed up H5N1's adaptation to humans.

Source: The avian and human influenza A virus receptors sialic acid (SA)-α2,3 and SA-α2,6 are widely expressed in the bovine mammary gland

Global Response and Preparedness

The global community is intensifying efforts to combat H5N1. On April 25, 2024, the WHO called for enhanced global surveillance of H5N1, expanding monitoring of other animal species and dairy products [11]. Amid growing concerns, the EU and the US have ordered vaccines to prepare for potential pandemics [12].

On June 10, 2024, the CDC issued a call for innovative diagnostic solutions, focusing on nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) [14]. On June 27, 2024, FIND launched a call for the development of H5 antigen tests, emphasizing the critical need for comprehensive diagnostics to control the outbreak [15]. On January 7, 2025, the FDA released draft guidance for validating certain IVDs for emerging pathogens, highlighting the regulatory approach to H5N1 diagnostics [16].

Conclusion

The widespread circulation of H5N1 among animals poses a significant risk of spillover to humans. Public health efforts must continue to protect workers exposed to infected animals through vaccination and diagnostics. Each human case must be thoroughly investigated to swiftly detect any mutations that may signal increased virulence or transmissibility. As scientists continue to study the virus, aggressive surveillance and pandemic preparedness remain crucial in preventing another global outbreak.

At Fapon, we vigilantly monitor epidemiological trends to swiftly deliver high-quality testing solutions to our partners. Our commitment to rigorous R&D and quality assurance ensures that we protect public health with precision. For inquiries regarding our H5N1 portfolio offering or other products, please contact us at market@fapon.com. Together, let's protect and safeguard global health.

Reference

[1] Peacock, T. P., Moncla, L., Dudas, G., et al. (2025, January 9). The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nature, 637, 304–313. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08054-z

[2] Cumulative number of confirmed human cases† for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2024. Retrieved from 2024_july_tableh5n1226acba9-e195-4ecf-8ef7-f00a93a06420.pdf

[3] Lee, D.-H., et al. (2015). Intercontinental spread of Asian-origin H5N8 to North America through Beringia by migratory birds. Journal of Virology, 89, 6521–6524.

[4] Lee, D.-H., et al. (2018). Transmission dynamics of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A(H5Nx) clade 2.3.4.4, North America, 2014-2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 24, 1840–1848.

[5] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/

[6] Ankerhold, J., Kessler, S., Beer, M., Schwemmle, M., & Ciminski, K. (2025). Replication Restriction of Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Viruses by Human Immune Factor, 2023–2024. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 31(1), 199-202. http://doi.org/10.3201/eid3101.241236

[7] Government of Canada. Statement from the Public Health Agency of Canada: Update on Avian Influenza and Risk to Canadians. Retrieved from http://www.canada.ca/en/public-health.html

[8] Peacock, T. P., Moncla, L., Dudas, G., et al. (2025, January 9). The global H5N1 influenza panzootic in mammals. Nature, 637, 304–313. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08054-z

[9] The avian and human influenza A virus receptors sialic acid (SA)-α2,3 and SA-α2,6 are widely expressed in the bovine mammary gland. (2024, May 3). bioRxiv. http://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.05.03.592326v1.full.pdf

[10] Emergence and interstate spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) in dairy cattle. Retrieved from http://www.biorxiv.org/

[11] 澳大利亚发现首例人感染H5N1型禽流感病毒病例,从海外输入!致死率超50%,上月美国出现全球首例“牛传人”. (2024, May 22). 每经网. http://www.nbd.com.cn/articles/2024-05-22/3399738.html

[12] US close to deal to bankroll Moderna bird flu vaccine trial. Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/content/fad59eb1-2f34-47eb-b938-49ed12f12c45

[13] Avian influenza overview December 2023–March 2024. Retrieved from http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AI-Report-XXVIII_0.pdf

[14] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, June 12). CDC Open Call to Industry for Influenza A(H5) Diagnostic Test Development and Validation. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/

[15] Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics. Lack of H5N1 influenza diagnostics undermines global pandemic readiness. Retrieved from http://www.finddx.org/

[16] Food and Drug Administration. Validation of Certain In Vitro Diagnostic Devices for Emerging Pathogens During a Section 564 Declared Emergency. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/